Many infrastructure investors have broadened their target investments beyond traditional core infrastructure such as highways and power plants. These core-plus infrastructure investments are increasingly centered around infrastructure technology products and services, or “infratech.” Infratech assets can take the form of software platforms, capital investments into technology assets (such as data centers, fiber, or systems of cameras and sensors), or entire integrated technical systems. These assets are supported by long-term contracts—so while they are technology investments, they retain the predictable cash flows of traditional infrastructure services. For example, electronic toll payments platforms and back-office software systems, which are increasingly finding their way into infrastructure funds, involve extended service contracts and reliable revenue streams.

As technology continues to transform the infrastructure sector, investors can find three main types of opportunity in infratech solutions. First, most opportunities lie in working with their portfolio companies’ management teams to modernize the operations of existing assets, helping operators meet infrastructure capacity challenges and reduce cost of operation. A solid understanding of infratech and upgrading existing infrastructure assets with new technologies can help investors successfully bid on traditional infrastructure assets where infratech might be incorporated. Second, they can invest in new infratech assets. And third, they can seek to own the technology companies that sell infratech and services, which typically win long-term contracts (ten years or more) to service infrastructure operators.

But while infratech brings new opportunities, it can also require a new risk-return model that shares some characteristics of traditional infrastructure investments yet differs in several ways. Infrastructure investors now need to understand technology, the risk of technology obsolescence, systems integration, and data integrity risk, whereas they generally did not before. And many investors and management teams require proof that solutions are viable before they are willing to invest the time and resources to implement these across their businesses. Management teams must choose between developing significant in-house capabilities or retaining a third party to manage integration of infratech solutions into their operating assets.

To capitalize on infratech opportunities, investors must step outside their comfort zones and consider which assets beyond traditional, core infrastructure assets to add to their portfolios. They must also bring a new set of technology partners into consortium structures to support their companies at the operational level.

This is a new endeavor with the potential for greater financial returns over the long run. We specifically explore three case examples involving different asset types to show what the financial impact could be to each investment, and how investors and asset operators can implement these changes, whether they are changes to tech solution packages, the tech partners they work with, or their operating models.

Technology’s outsized impact on infrastructure

As technology transforms how infrastructure fulfills its role, it has altered the economics of certain assets—and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this trend. Owners of affected asset types—such as parking garages, which faced significantly lower demand even before the pandemic (as shown in the case study below)—are left scrambling to find ways to bolster their bottom line and chart a future.

Six trends together are creating a new paradigm for the funding and operation of infrastructure assets (Exhibit 1). Some of these trends are already making their impact felt—cybersecurity is currently one of the biggest risks to asset operations. For example, the cost of cybercrime to the global economy was estimated as high as $575 billion in 2016.1 Other trends, such as the impact of automation and the real-time monetization of assets through data analytics, will start to increasingly take effect in the coming years.

Underlying these trends are more than 70 individual technologies, which each have the potential to disrupt some—or many—parts of the sector within the next 15 years (Exhibit 2). These technologies will be significant for owners as a source of enhanced operations and for investors as a new form of asset in which to invest. The impact of some of these—such as e-hailing solutions and online lodging marketplaces—is already being felt. The impact of other technologies, such as autonomous vehicles, electrification of vehicles and industrials, and new transmission and distribution required for renewable energy, is expected to appear around ten years from now.

Taken together, these technologies and trends are likely to significantly disrupt infrastructure across all asset classes in three broad ways:

- Creating new investable capital opportunities: Infratech solutions offer those investors seeking new assets or core-plus opportunities a wider portfolio of potential deals.2 For example, we estimate that by 2022, more than $1 billion of smart water meters will be installed globally.

- Setting new standards for asset developments and concessions: Governments are proactively starting to update their technology requirements for safety, environmental impact, and cost in proposal requests; those bidders who incorporate infratech solutions will be more successful in winning these concessions, setting a new bar for market-leading concession and asset development deals.

- Changing the revenue and cost structure of asset operations: Technology is changing the cost structure and revenue potential of assets. For example, real-time data analytics can facilitate dynamic toll pricing systems that increase tolls during peak hours, which can boost revenue while discouraging use and, therefore, alleviating highway congestion.

How operators and investors must both adapt

To navigate this disruption and access the new opportunities at the intersection of infrastructure and technology, operators and investors should start by mapping the new, expanded infrastructure asset space and revisiting their strategies. That means understanding an asset’s readiness to deploy an infratech solution and understanding the economic implications (including those for capital expenditures, operational expenditures, and revenue) of embedding technology into their existing assets. Pivoting toward these new infratech assets comes with a series of challenges for both investors and operators.

For investors

Investors will need to move away from the notion of infrastructure as merely physical assets in order to capitalize on the infratech opportunity, which will likely require new stakeholder mindsets and internal advocacy for emerging infrastructure business models. While not unproven, infratech is in its early stages, and investors may be concerned about a number of associated risks, such as cybersecurity or the potential for disruptive forces to render assets obsolete. And while many infrastructure investors may recognize the need to invest to spur innovation, they may lack the data and technology expertise to make decisions with confidence and monetize assets and platforms. Furthermore, they may face external challenges; for example, they may need to educate governments on the benefits of adopting new technologies where tender processes have not yet evolved to value infratech.

For operating companies

As with investors, operators will need to take stock of their capabilities, particularly the technological knowledge to deploy and operate infratech assets. They will likely need to fill in-house gaps (such as data analytics) and work with new technology partners (such as smart tech manufacturers and developers and design consortiums) that can build, implement, and comanage these enhanced capabilities. For an industry that’s been slow to adopt new technologies, maximizing the potential of infratech will require significant shifts in mindset and ambition.

Both investors and operators will need to become comfortable with a new risk-return model. Whichever route they choose, infratech introduces new risks, such as the consequences of the limited life span of technical hardware (for example, cameras and sensors) and shifting technology partners (many firms are new and might not last). When partnering with technology companies, investors and operators will need to have explicit discussions about the distribution of risk. They must clearly define, for example, who assumes the revenue risk for dynamic pricing platforms in smart highways and parking garages; for unproven assets, one solution may be to share the risk with owners through upside incentives.

Case studies showing three potential infratech investment areas

To demonstrate the magnitude of the opportunities available—and the sorts of technologies that fall under the infratech umbrella—we present three case studies of infratech investment opportunities. Each case is based on opportunities that are fully realizable today. The economic benefits estimated here are based on research, interviews, lessons from client engagements, and a detailed review of the actual technologies; specific financial estimates are based on analysis of the capital expenditures, operating expenditures, and revenue implications of specific technical solutions.

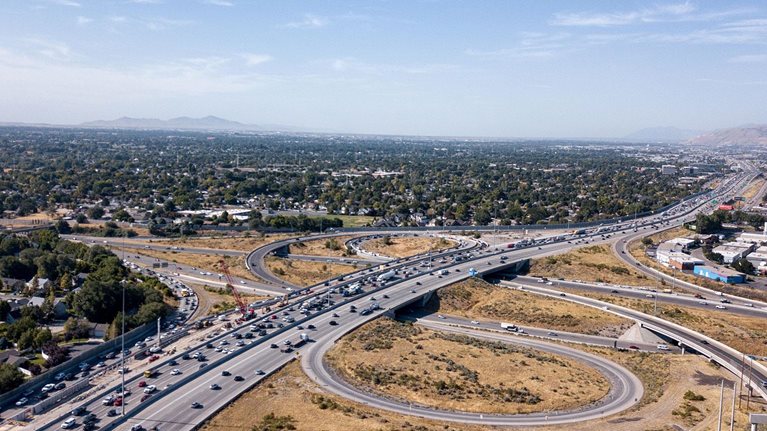

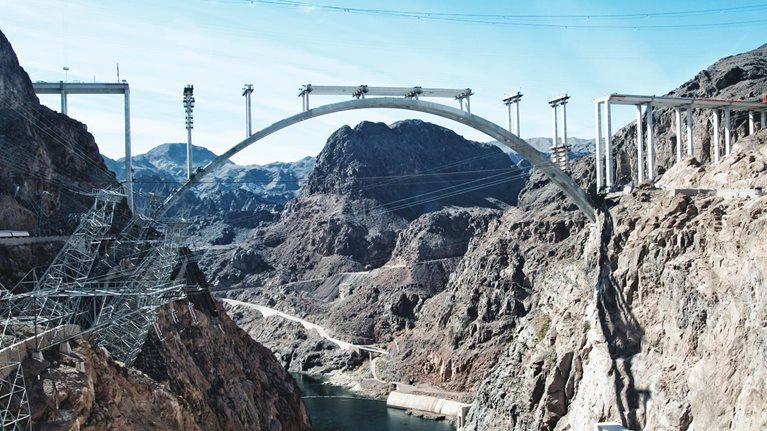

Smart roads

In a select few cities around the world, smart roads are already a reality, but the actual technologies installed and their use vary drastically, leaving substantial room for advancement. A case in point: although the automatic-payments systems behind tolling technology are widely implemented around the world, dynamic tolling systems are still rare and even face public resistance in some locations.

The disruptive tech. The roads of the near future will include intelligent traffic systems and will support new modes of transport such as electrical and autonomous vehicles (Exhibit 3). Sensors and cameras will collect traffic conditions, curbside monetization will adjust usage or space based on demand, dynamic road signage will update based on road conditions, and drone monitoring will enable predictive maintenance. The intelligent traffic systems will be designed to fully integrate electric vehicles, ridesharing platforms, and even air taxis. These smart road solutions will come online gradually as the technology develops. Intelligent transportation systems, for example, are already being deployed through the fiber broadband network, and dynamic pricing is being used to relieve congestion in regions where there is political acceptance of this billing model. The infrastructure needed to support autonomous vehicles, on the other hand, is not expected to come online in a significant way within the next five years, although several pilot programs have attracted a great deal of attention.

The opportunity. Taken together, upgrading roadways with smart tech presents a new investment opportunity of at least $650 billion globally by 2025. Of this, around $530 billion will come from upgrading the $10.6 trillion existing road asset pool, and around $120 billion will involve installing smart systems into new roads.

How to invest and the potential return. Tolled highways make sense as the first targets for smart technology investment. According to our research, they present the advantage of a clear monetization model and make up a significant proportion of planned and ongoing road infrastructure investment between 2020 and 2025. This opportunity applies to both public road agencies and private operators. Investments in these tolled, smart highways can offer a strong return on capital; if smart road investments were applied to the Tennessee I-24 Parallel Interstate, for example, that could almost quadruple the net present value of the road to $64 million from $17 million (Exhibit 4).

Case examples. In the city of Boston in 2014, for example, traffic jam data from the navigation app Waze was used to identify problematic intersections in the Seaport District.3 The city’s analysts studied signal timing, experimented with adjustments, and then measured the impact of each adjustment. After implementing the most impactful changes, they recorded an 18 percent congestion reduction at key intersections.

In 2012, the US Department of Transportation awarded a $10 million grant for the New Jersey Transit Authority to install an adaptive control system—that uses wireless and fiber-optic network communications—on 123 traffic signals within the Meadowlands region. To install this system, the transit authority had to add advanced traffic signal control components to existing signal cabinets; mount vehicle-detection cameras, radios, and antennas; and install wiring to serve them all. They estimate that the system serves more than three million vehicles each day and has reduced traffic delays by 1.2 million hours per year. It has also reduced greenhouse gas emissions by more than 11,000 tons per year. To put this in context, that savings is equivalent to the CO2 emissions of 7,000 to 30,000 four-hour aircraft trips every year.4

Smart parking garages

Parking garages are an asset class that is already seeing disruption and changes through mobile technology and changing consumer preferences, as well as a drop in demand for parking as the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically reduced personal car travel in 2020. However, integrating new infratech into parking garages could expand the business model to accommodate new revenue streams, improve user experience, and reduce operating costs (Exhibit 5).

The disruptive tech. Dynamic parking tariffs could be used to optimize utilization and revenue, for example, and charging infrastructure for electric vehicles (through energy sales) and retrofitting of parking space (for instance, as space for mobile kitchens to operate) would add new revenue streams. Automating many aspects of parking operations presents the opportunity to improve utilization efficiency and lower operating costs; intelligent parking guidance systems could be used to direct drivers to an available parking spot with the right facilities and, if connected to a mobile payments app, that spot could be booked by a commuter before they even leave their driveway. Some of these solutions are already online; intelligent parking systems, app-based payment platforms, and car parking reservations will be widely deployed within the next five years, for example, as will dynamic parking tariffs. Other technologies, such as the complete upgrading of charging infrastructure to accommodate electric vehicles, will not be fully implemented for another five to 15 years, and unmanned aerial vehicle technology (and its supporting facilities) is likely to take longer still.

The opportunity. As mentioned, the disruption presented by ridesharing is sharply impacting parking revenues, particularly for assets at airports and central business districts. Interviews with industry players indicate a likely 20–30 percent anticipated drop in revenues for some assets in the next five years (through 2025) due to micromobility and services such as ridesharing. One car-sharing vehicle can take as many as 13 private cars off the road while reducing vehicle miles traveled by 27 percent.5 The rise in popularity of cycling and scooters also reduces demand; one curbside parking space can be used for eight to ten bicycles. Despite this, we estimate that smart parking garages can increase the net present value (NPV) of a traditional parking garage investment by a factor of approximately 1.5 (Exhibit 6). The ability to generate additional revenue streams will be vital for the segment because parking garages are highly susceptible to these disruptive trends. Without the development of the new revenue streams facilitated by infratech, owners may find that it would be more profitable to repurpose their assets into higher-value products such as residential developments.

How to invest and the potential return. Existing owners of parking garages need to review their portfolios to identify which assets are at risk from disruption. While some assets may maintain robust parking demand, many will need to invest in retrofitting their assets to generate alternative sources of revenue. Operators are already looking into so-called dark kitchens (delivery-only restaurants), electric vehicle charging, and even offering parking deals to rideshare drivers waiting on their next commission. It is possible to realize a positive economic return on these investments; an analysis of NPV showed that it is possible to completely offset the lost revenue from disruptions and even improve the value of the asset to 1.5 times the asset’s NVP (after accounting for disruptions) by applying smart technology (Exhibit 6).

Many of these ventures will require fresh capital injections—an opportunity for investors looking to partner with or buy a parking operator. For assets with robust parking demand, there is still the opportunity to invest in technology to automate operations to reduce operating cost. There is also opportunity in developing or buying remote booking apps to increase parking-space utilization and customer convenience. For new parking developments, the investment thesis should be completely revisited, looking to reduce the parking footprint and integrate technology and apps from the start to maximize value created. For those not willing to pursue any of these options, an exit from their underperforming assets may be the best way forward.

Case examples. In 2015, the city of Frederiksberg, Denmark, aimed to increase paid parking to 20,000 spots from 12,000 and to increase the number of residential permits by using mobile payments and digital permits. Sixty-seven percent of citizens chose phone parking as a preferred payment method, and transactions in parking payments increased by 50 percent in the first three months after implementation.

In March 2019, Stanley Robotics and Aéroports de Lyon/VINCI Airports developed a partnership in France’s Lyon-Saint Exupéry airport’s P5+ car park. At this car park, drivers stop their vehicles inside a general parking space, after which an autonomous robot pulls and repositions the car into a compact set of parking positions (like a tugboat in a port). At the time of implementation, four autonomous robots operated simultaneously to serve 12 vehicle drop-off, pickup boxes and fill 500 parking spaces. The plan is to deploy more robots to cover an additional 2,000 spaces by 2020. Customers benefit from the convenience of simply dropping off their vehicles and going about their business without having to search for a spot and then squeeze in. And the robots increase the efficiency and revenue potential of a particular parking area because they can fit a far larger number of vehicles into the same space than human drivers.

Automated waste collection

Automated waste collection systems (AWCS) would allow urban waste to be collected and sorted automatically (Exhibit 7). Collection points will allow users on the street—or in buildings—to drop presorted waste, which will travel along an underground pipeline (by pneumatic pressure) to a remote collection terminal, where it will be compacted and fed into containers to be removed by trucks.

The disruptive tech. These sorts of systems use proven technologies and can be highly profitable; over the past 40 years, more than 2,000 AWCS have been installed around the world, including in a greenfield real estate development in New York City’s Hudson Yards, in sports facilities in Moscow, and in the Hainan Cancer Hospital in China. Yet general awareness of this technology remains low, and the potential for future rollouts is immense.

The opportunity. AWCS create value for governments and investors; we estimate that municipalities can save 25–35 percent on waste collection over a 30-year period, while investors can capture returns of 5–25 percent by building and operating an AWCS over the same period.

Over the next eight to ten years, the market is projected to grow by 15 percent, with more than 250 new systems—requiring $2.5 billion in investment—to be installed around the world. Looking forward, the estimated global opportunity around AWCS adoption is considerable, particularly in Asia (Exhibit 8); just implementing AWCS along public spaces in existing downtown municipal areas (such as sidewalks and parks) and bringing connection points to privately owned assets such as residences and offices may be worth up to $400 billion in investment globally.6

How to invest and the potential return. Given the large potential opportunity, investors will need to consider how to choose where to invest. The overall AWCS market opportunity can be segmented based on particular risk criteria or preferences. Investors looking to work with governments that are environmentally friendly, for example, will have opportunities in the 340–360 municipalities where local governments have an environmental performance index (EPI) of over 60, and the total size of this opportunity is around $20 billion to $140 billion.

Investors who require a stable power supply will have more than 600 municipalities to choose from, and a total opportunity size of around $50 billion to $240 billion. Even investors with stringent requirements across criteria will have numerous available opportunities; investors looking for opportunities that involve high capital expenditure in cities that have a high population, wealthy inhabitants, high congestion, stable power, and an environmentally friendly government will still have nine to 38 municipalities to choose from and an opportunity size of $4 billion to $33 billion.

Case example. The central business district of Maroochydore City Centre, Australia, is densely populated, with more than 2,000 apartments, retail outlets, and a significant amount of retail space in just 53 hectares (0.53 square kilometers). The first phase of a new AWCS was completed in 2019; when the project is complete, a capital expenditure of AU $21 million will have been spent on 300 new waste inlet points and a pipe network of 6.5 kilometers to move both general waste and dry recyclables to a collection terminal. In addition to the city’s expectations that user recycling rates will increase and the cost of daily street cleaning will go down, they expect to also create 15,000 jobs over the life of the project through the construction and operation of the facilities.

Looking forward, infratech opportunities could draw $500 billion to $1 trillion in investment over the next five to ten years—if their full potential is met. Realizing those opportunities will be a challenge. It will require strategic thinking about what assets can be included in funds, enhanced efforts in finding potential investments, and building partnerships with technology players across the value chain.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that all types of players are going to move toward these kinds of investments: governments that want to include them in their assets, operators who want to meet government regulations, investors that want to differentiate their bids, and tech companies that are trying to find more users for their services. The market is nascent and is yet to be shaped. Capitalizing on this opportunity requires players to not only demonstrate the impact but also scale it up to a wider portfolio of assets. They must work to integrate the different tech components into a business solution.

These are all challenges, to be sure. But the end result is worth it: in some cases, 15–20 percent margin improvement for an asset. Those who act sooner will have more opportunities available to them.